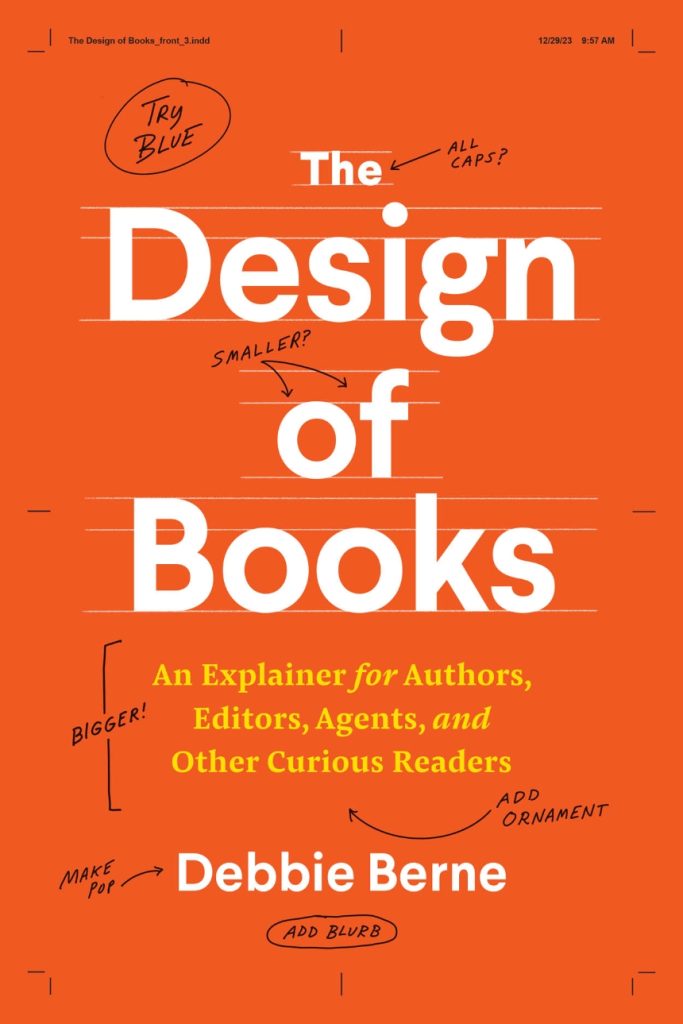

Over the winter, my sister-in-law (also a writer) loaned me The Design of Books: An Explainer for Authors, Editors, Agents, and Other Curious Readers, by Debbie Berne. After racing through it, impressed by the way it visually proved each point through its own deceptively simple design, I immediately bought my own copy—and have referred to it frequently over the past few months, as I work with the designer to lay out the Hound book.

As Berne points out, the best book design blends into the background, unnoticed by most readers. Here’s an excerpt from the first chapter:

A book page is so familiar, and seemingly so straightforward, there may not seem much for a designer to do. But a lot of thinking goes into even the most basic page of text. The work is labor-intensive, fussy, hidden, and yet transformative . . . When this is done well, the mechanics of the writing and the design virtually disappear.”

Words Matter

Naturally, over the centuries, book designers have developed their own language (just like sailors). This book defines several terms that I’d never really understood. In book-speak, what I think of as “a book” is properly called a codex: to distinguish it from a tablet or scroll. There’s a reason this structure has stood the test of time, says Berne. “A codex is handy, sturdy, and easy to use. It allows for random access—you can open it to any part—in contrast to scrolls, which much be unwound and sifted through sequentially. Pages can be printed on both sides, creating efficiency in their manufacture and their use.”

Another favorite bookish term is now “folio,” which sounds so much more impressive than “page number.” That is not to be confused with “spread,” which is both of the folios you see when the book lies open. There are also running feet, running heads, and even running shoulders; all help form that “unseen” structure that guides our eyes across each page.

Joys and Pitfalls

But this book is far more than just a dictionary. Berne has worked with both traditional and self-published authors, and she shares both the joy and potential pitfalls of that inevitable moment when lofty ideas first meet on-page reality. Under Sample Design, a term she calls “vanilla” for “what may be the hardest and most important (and most exciting) phase of book design,” she explains:

“Design brings shape, structure, and pacing to a project. It’s not unusual for authors to tell me that everything became so much clearer once they saw some portion of their manuscript in designed spreads. ‘Ah! That’s what I’ve been doing!’ Design can illuminate the relationship (or, at least, one possible relationship) between words and images that authors have suspected but haven’t been quite able to grasp.”

Berne also points out something that definitely hit home with this author: Editors “worry that authors can’t stop revising, and some can’t.”

No Micromanaging

For me, the most valuable part of the book was some firm direction on how to provide feedback. It’s advice that could be applied to any working relationship, but it really helped me communicate more efficiently with the designer. The two most important points were:

1. “If there are aspects you think you don’t like or may want changes, start by asking the designer WHY they made the choices they did.” (Emphasis mine.)

2. Focus on overall impact. “Know that the details will be worked out in the designing and should not be overdetermined or micromanaged. I can’t say it enough times: leave the designing to the designers.”

More than a Manual

Throughout the book, Berne’s humor and knowledge weave together into another unseen feature of the best books: a distinctive voice. Combined with the deceptively simple layout, her creation became for me much more than just another how-to: reading it actually quieted my brain. It was a comforting reassurance that there is structure in the world—at least the one that lies between these orange covers.

Some books find us at exactly the right time, and thanks to the The Design of Books I now understand why the Hound book designer wanted to design the cover before the interior (sorry). So thanks to Debbie Berne for putting together what she calls “a book that is accessible and useful (and even a little bit fun),” an invaluable addition to my library as both a calming and comprehensive guide—just in time to make an “unseen” difference to my next book.

Also thanks to my sister-in-law for loaning out her copy!

Got a question about book-building? Add it to the comments below, or send me an email. I read every single one, with gratitude—and I’m so glad you’re here.