Islands, as one of my minor characters points out, are “such a metaphor for our lives, yanno?” Their isolation is both a blessing—a key part of our winter escapes—and a curse, now that a trifecta of hurricanes have washed away Caribbean boats, houses, leaves, and most everything else.

Vacation mode

Thirty years ago, I spent two months sailing around the Caribbean, long enough to watch several weeks’ worth of winter visitors come and go. Since then, I’ve gone back whenever I got the chance, joining the ranks of those weeklong vacationers. Each year, I’d discover a jetski rental in another formerly remote anchorage, or a favorite beachside beer hut that now offered icy umbrella drinks and goat cheese salads. On some islands, light pollution began to interfere with stargazing. (Of course, there were also an equal number of improvements: a wide variety of food options, reliably hot showers, cockroach-free dining.)

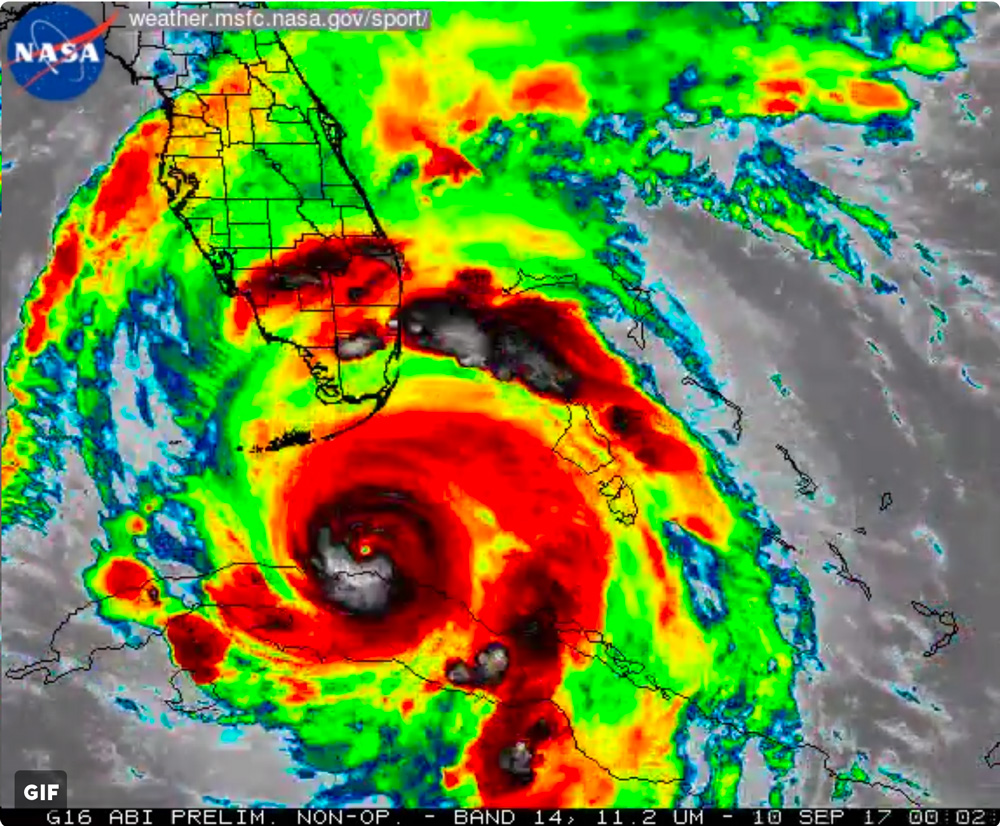

Now that Irma, José, and Maria have stripped away those thirty-plus years of “progress,” I’ve been wondering: what’s next for the islands that have so reliably provided us all with a winter escape hatch?

The devastation of so many favorite places at once is completely overwhelming. As sailors, we were first told to show up as usual (for spring regattas that are still on the schedule) and then, a few days later, instructed firmly to stay away (as cruisers who might consider crashing the recovery party). Other than send as many dollars as we can afford, what should we do?

Here’s what I know

- Development will happen all over again, even though it’s only a matter of time before the next big storm washes and blows it all away. Our desire for fine drinking and dining beachside will once again encourage shoreline “improvements.”

- “The Caribbean” is actually a collection of fiercely independent nation-states. Each island will adapt to the new reality differently; some will make longer-term plans, while others will simply rebuild the wreckage into something useable again, as quickly as they can. Leadership will vary, which will affect recoveries in both timing and quality. It will be years before we’ll be able to say who did things best (though responses to past storms will be reliable indicators).

- The can-do attitude of locals will enable them to rebuild faster (though perhaps not better) than we expect. In October of 2016, sailing a regatta in Nassau less than ten days after Hurricane Matthew’s eye passed right over that island showed how islanders make things happen.

- You can’t keep the gringos away. Caribbean winter sun and fun will continue to attract us, for as many days or weeks as we can manage each year. As the most reliable source of income, vacation-mode attractions will continue to dominate the local economy.

Local choices

Part of me wishes the islands could remain “unimproved.” How many jetski rentals and goat cheese salads do we really need? But that is neither realistic nor fair to the people who live in our vacation paradise year-round. The locals have a right to make a living, and an “improved” coastline will attract more vacation dollars than palm trees and sand.

What’s happened in tropical paradise is too big and too complicated to absorb, so for now I’m going to focus on one simple thought: I can’t wait to see what all those resilient Caribbean islanders will do with their future.