I’ve long admired author Jodi Picoult for daring to delve into topics that don’t have any simple answers. In her twenty-fifth novel, Small Great Things, the theme is unconscious bias. Though this term is now in common use, I’m guessing that when Picoult first sat down to write this book (published in 2016), it was not. Which makes me wonder if this work of fiction has helped bring to light how the world really works.

The main character is Ruth, an experienced nurse who happens to be the only African-American working in labor and delivery at a small hospital in New Haven. When Ruth tries to examine a newborn, the white supremacist father requests that she not touch his son and complains to a supervisor; Ruth is reassigned. Then the baby goes into cardiac arrest, Ruth tries and fails to resuscitate him, and the father accuses Ruth of murder.

The main character is Ruth, an experienced nurse who happens to be the only African-American working in labor and delivery at a small hospital in New Haven. When Ruth tries to examine a newborn, the white supremacist father requests that she not touch his son and complains to a supervisor; Ruth is reassigned. Then the baby goes into cardiac arrest, Ruth tries and fails to resuscitate him, and the father accuses Ruth of murder.

The public defender who takes Ruth’s case insists that mentioning race in the courtroom will only make the jury unsympathetic, so Ruth is forced to battle with her own conscience as well as a murder trial; is it worth going to jail, just to have her say about what it’s like to be a Black woman? (I capitalize Black intentionally, just as Picoult does—but only in the chapters told from Ruth’s perspective.)

I was already drawn into the story by the time I realized that Ruth would not be the only narrator. Just after Turk, the white supremacist dad, throws Ruth out of the delivery room (but before his son dies), we begin to see the world through his eyes. How much he loves his wife and son. How much he hates African-Americans (though he uses a very different word), and anyone else born without pure white Aryan blood. It is sickening to read, and yet Picoult manages to make Turk sympathetic, both by forcing us to walk in his shoes and by allowing him to change. (His ending, based on a real-life experience, is perhaps the most surprising of all.)

The third point of view is Kennedy, Ruth’s lawyer. She chose to become a public defender because she wants to help people; “I was never going to get rich, but I’d be able to look myself in the eye.” She can afford this choice because of her surgeon-husband’s salary and support; he tells her, “I’ll make the money, you make the difference.” But by the time we meet Kennedy (yes, she was named after JFK), she has realized that the system itself is a large part of the problem. As she gets to know Ruth, she also begins to see how much that system—fueled by both conscious and unconscious bias—has helped her go about her own life and raise her daughter without the endless, gut-punching fear that Ruth and her son take for granted as part of the everyday. Kennedy doesn’t pretend to find answers by book’s end, but she does learn to see herself in a very different light.

Somehow, the story is never without hope—even as each character acknowledges the insurmountable challenge of achieving racial equity. Not equality, Kennedy corrects Ruth:

“Equality is treating everyone the same. But equity is taking differences into account, so everyone has a chance to succeed.” I look at her. “The first one sounds fair. The second one is fair. It’s equal to give a printed test to two kids. But if one’s blind and one’s sighted, that’s not true. You ought to give one a Braille test and one a printed test, which both cover the same material.”

Since most of Picoult’s readership is white, I’m guessing most (like me) will find Kennedy’ point of view familiar. I also like to think that others (like me) will be able to “see” the world through the eyes of an African-American nurse and a white supremacist, because only through well-written, thoughtful fiction like this can we world-jump inside our heads to a place where we are the ones who look different.

I do have one quibble; the overuse of medical techno-jargon, especially in early chapters. Maybe Picoult and her editors thought they were showing Ruth’s experience and competence, but for those of us who have no idea what all those acronyms mean, they don’t establish credibility—all they do is distract from the story. This small complaint is definitely outweighed by such an excellent mix of entertainment and education; I will be thinking about this book for a long, long time. I recommend it to anyone who, like me, spends most of her days surrounded by people who look the same, because this book will make you realize that is a privilege rather than a right.

The title is taken from a quote that, as Picoult says in the excellent author’s note at the end, is “often attributed” to Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr: “If I cannot do great things, I can do small things in a great way.” I’m taking this story as much-needed inspiration, to do a few small things in my world that will help everyone achieve their dreams.

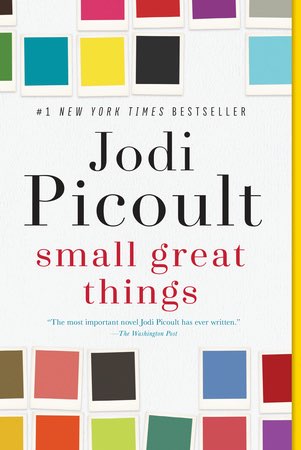

PS: I didn’t realize until I sat down to write this review and looked at the cover in detail: it is a bunch of color chips. And “white” is missing.