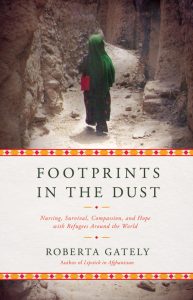

Full disclosure: I don’t read a lot of memoir. I might not ever have stumbled onto Footprints in the Dust if its author, Roberta Gately, hadn’t first written two novels: Lipstick in Afghanistan and The Bracelet. Her lovely memoir comes out October 2nd, and I was lucky enough to read an advance copy.

For more than twenty years, Gately arranged her “regular” career as an ER nurse in Boston around her true calling: helping refugees who’d fled their homes and left behind (as she puts it) “everything but hope.” For months at a time, she went where she was needed most—Pakistan, Afghanistan, Darfur—helping those who’d been displaced and wounded by wars that barely made the news back in the US. Even though she always seemed to pack the wrong clothes for the weather, she never shied away from a challenge; for one assignment, she even adopted a different passport (and accent) so she wouldn’t be targeted as an American.

Gately tells a great story, so we taste the dust and instant coffee, smell the latrines, and miss the wine and pizza right along with her. And even at the worst of times, we’re reminded of both beauty and humanity; our narrator’s positive warmth and belief in basic goodness always shine through.

In each location Gately clearly describes the challenges, but the focus is on her friends and patients (people she still carries in her heart, years later), and she describes them all so vividly that we feel like we’ve met a few of the world’s twenty-two million refugees. At their clinics, women and children were treated first, Gately explains; “Tradition in so many of these places required that men be first in everything—food, shelter, education—but these women and children would always come first for me.” On an early assignment in a small Pakistani village, Gately talks about meeting an older woman who used to be “somebody important,” and goes on to explain the wide gulf she needed to cross each time she met with a patient:

I couldn’t even imagine how hard it must be for these women who had been forced from their homes, from everything they knew. Their children—if not injured or sick—were hungry, their husbands at war, their land lost, their homes destroyed. How could I, how could any of us, who would all eventually go home to warm, safe homes, ever really know the extent of their suffering?

This is what memoir was meant to accomplish; by air-dropping us into history, it shows rather than tells through a single, carefully focused perspective, helping us to understand people we’ve never met.

I found the final section a bit repetitive, which made me wonder whether the author’s (or editor’s) enthusiasm had simply been worn down by such an endless stream of need. Over Gately’s decades of dedication, international aid work evolved from casual to structured, but that didn’t resolve the refugees’ problems. Even for such an optimistic angel-nurse-bulldog, trying to meet the same basic needs (food, clean drinking water, medical supplies, shade) over and over and over again must’ve been emotionally exhausting. But Gately doesn’t ever let herself wallow; even when faced with her own medical challenges, she focuses on others—and is eventually rewarded by the signs of progress she finds in a small village, months later, when she manages to visit once again.

As the book copy states, “Footprints in the Dust reveals the humanity behind the headlines.” By mining her memories and applying her storytelling talents, Gately has brought nameless, faceless refugees to life. She’s shown us the people torn from their homes by devastating political decisions, all while holding up a mirror to our commonality. “The only thing I need now,” one of the refugees tells Gately, “is to go home, to work in my garden again, and to die in my own land.”

For more, and to order your copy of Footprints in the Dust, visit Roberta Gately online.