Thanks to a recent house project, I’ve been thinking a lot about what books I like enough to shelve after reading. Their topics and genres range widely, but they all share a strong opening; one that somehow tickles my memory follicles, embedding the story in my brain long after I devour the last page.

Here are three very different examples, along with my thoughts about what works (or not) in their opening chapters.

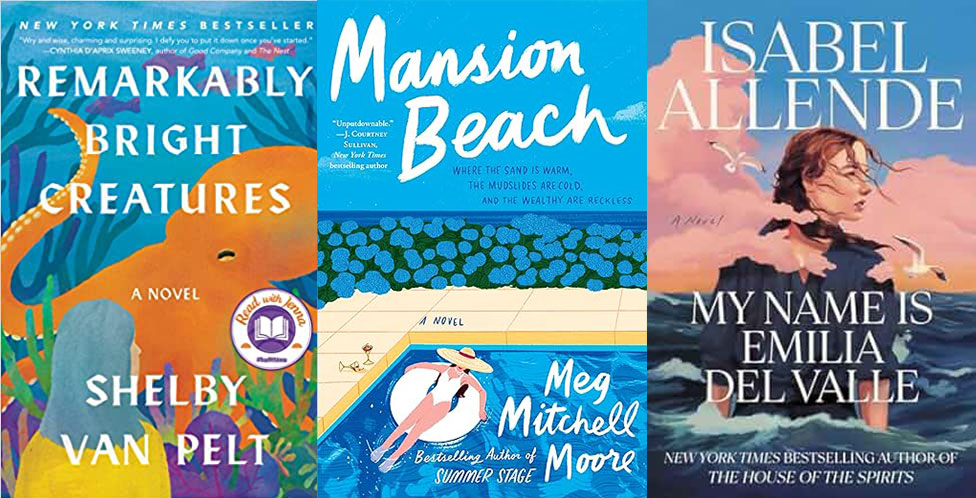

Remarkably Bright Creatures, by Shelby van Pelt

I read this book when it first came out in 2022 (here’s my review) and then reread it a few weeks ago for book group; once again, I found myself torn between devouring the story and marveling, “How did Pelt do that?”

It opens with an octopus explaining his plight: he’s captive in an aquarium tank that makes him long for open ocean. “I cannot remember, yet I can still taste the untamed currents of the cold open water.” He talks to us directly, adding that he will not hold our inadequate imaginations against us; “You are only human, after all.” He also sets up a unique ticking time bomb, citing the plaque on his tank that gives him only 160 days to live—because yes, he can both read and count.

What this opening achieves: The first chapter is only 500 words long. But thanks to its distinctive voice and implausible storyline, the story has already wrapped octopus arms around my brain.

What this opening fails to do: It doesn’t show us the larger context / world—which makes me hungry to learn what happens next.

Mansion Beach, by Meg Mitchell Moore

I’ve been a MMM fan for years, fueled by her impressive book-a-year publishing pace. Her 2025 beach read (once again set on Block Island) starts off, strangely enough, with a prologued podcast transcript:

“Welcome to Life and Death on an Island, produced by All Ears Media. I’m your host, Milton Anderson, and on this podcast we’re taking taking a deep dive, so to speak, into life on a small island whose population increases nearly twentyfold from winter to summer.”

The episode interviews four members of the Town Council; “Some of these members believe a mysterious death last summer was related to issues of overdevelopment, landownership, and excessive lifestyles on the island.”

What this opening achieves: Sets up the book’s central question: who died? It also shows us the book’s future, while introducing us to multiple points of view; a precursor to the book itself.

What this opening fails to do: It doesn’t introduce us to the characters who actually tell the story, people we will quickly grow to care about (unlike the podcast’s talking heads).

My Name is Emilia del Valle, by Isabelle Allende

Allende opens her latest novel with a childhood memory from the sole point-of-view character:

“THE DAY I TURNED SEVEN YEARS OLD, APRIL 14, 1873, my mother, Molly Walsh, dressed me in my Sunday best and brought me to Union Square to have my portrait taken. The only existing photograph of my childhood depicts me standing beside a harp with the terrified expression of a man on the gallows, a result of the long minutes spent staring into the black box of the camera holding my breath, followed by the startle of the flashbulb. I should clarify that I do not know how to play any instrument; the harp was merely one of the dusty theatrical props crowded into the photography studio alongside cardboard columns, Chinese vases, and a stuffed horse.”

What this opening achieves: Unlike the previous two books, we start with the main character’s past, in what could be an unremarkable situation. But because it happens first, our reader-brains unconsciously give it weight—and that turns out to be a wise assumption. It also reveals a reporter’s wish for accuracy, thanks in part to four seemingly insignificant words; “I should clarify that . . .”

What this opening fails to do: We don’t know where this scared young girl will take us, though we do know it will take a lot of lyrical writing to get there.

These three very different books all begin with seemingly insignificant details that don’t quite satisfy—but all set up the book’s central question, which fuels our hunger to find out what happens next. Regardless of genre, the best openings trust the reader to make a few leaps of faith—a trigger for our memory follicles, which will help to embed the story in our brains long after we devour the last page.

Have you read something recently that you can’t stop thinking about? Share it in the comments below, or send me an email. I read every single one, with gratitude. See you next Thursday!