Over the past few months, while paddling along the familiar shoreline of Narragansett Bay, I’ve been watching the ocean grow. Rocks that have proudly protruded above the surface for the past twenty years (except, perhaps, during a beautiful super moon) now disappear for an hour or so on a regular high tide. By trusting my own senses, I’m seeing changes in sea level right in my own back yard.

Ocean Science

I’m a writer, not a scientist, so the only reason I understand the root causes of my casual observations is that I’ve listened to the “doctor of fish.” John Manderson is a fellow sailor and longtime friend who works with both NOAA climatologists and fishermen to translate real-time data into future policies, and he often stays with us when he’s working in Rhode Island. Our free-flowing evening conversations range from grammar to grandparents to Greenland (which, by the way, may soon be turning green). And then inevitably, the topic always returns to this: the changes we’re seeing in our preferred playground, the ocean.

Several years ago, John told us about the butterfish changing its Atlantic migration pattern. This species had effectively voted with fins and tails, making a new home wherever its preferred water temperature could now be found. Like a coal mine canary, these fish signaled changes too subtle (and too large-scale) for even the most observant coastal writer to see.

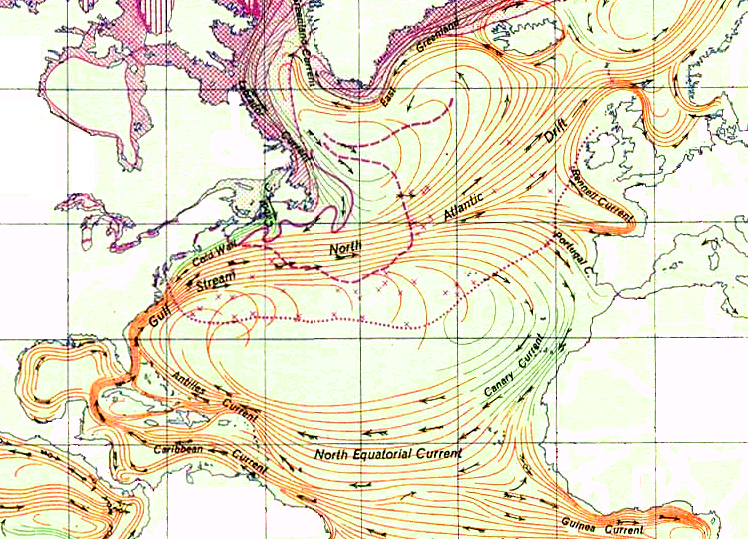

One year ago, John shared a shocking bit of data: the Gulf Stream (something I’ve always taken for granted as a constant) is measurably slower today than it was five years ago. Egad.

And then just the other night, he told us about watching glacier melt in Iceland pour down from the mountains into the sea. To grossly oversimplify a very complicated topic, all that fresh water flows out to join the Atlantic gyre—and then pushes up against the east coast of the US, covering the rocks in my local harbor.

“I’ve mostly stopped talking about it,” John says. He’s tired of trying to explain that so-called “king” tides will soon be the norm.

What to do?

So what can we coastal dwellers do, now that these big picture changes are actually visible? According to John, it’s already too late to do much more than follow the lead of the butterfish, voting with our own fins and tails by changing our migration patterns. As a perennial optimist, though, he also suggests adopting less carbon-intensive habits. “Imagine if we all changed our light bulbs to LEDs, put up solar panels, rode bicycles more than we drove cars, ate from local farms and fishermen… There is hope in action by all of us, more so than in the glacial movements of those in power, who are unfortunately much slower than the rate of melt of the Greenland ice sheet.”

Sea level isn’t an exact fixed number anymore. Narragansett Bay and her big sister, the Atlantic Ocean, are not the stable, dependable bodies of water I’ve always taken for granted: they are growing before our very eyes. Fortunately, there are many, many smart people like John who can explain the underlying reasons for the changes I’ll see on my next paddle. All I can do (besides trying to reduce my own carbon footprint) is to trust my senses, open my mind, and listen.

Excellent post, and hopefully is some small way this will open your readers eyes to what is happening.

Hope so!

Nothing like an INFORMED observer as opposed to mere perception/interpretation, the latter a very present problem. Anyway, nicely, engagingly written. Make sure the Town Council gets a copy. With no action we’ll have three islands rather than one.

Richard, Thanks for the note. Unfortunately I think the town council might fall under the category of what John calls “glacial movements of those in power.”

Thought-provoking…..

We raised our dock 18″ a few years back and it’s not enough. Ask Downtown Annapolis how they feel!!