Twenty-six years ago I made the colossal leap from typewriter to computer, a transition so liberating it is quite simply impossible to imagine ever going back. Suddenly my fingers could keep up with my imagination and typos could be dealt with after the story was captured! Look ma, no whiteout.

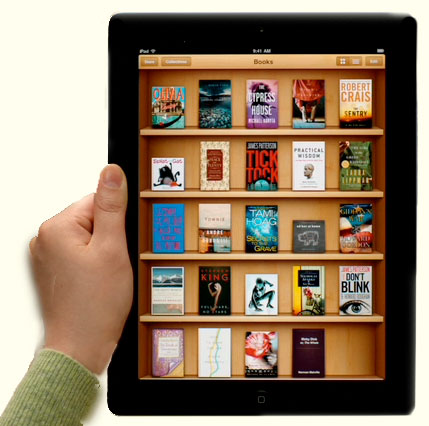

And now I face another colossal leap. The ebook revolution offers a dizzying array of options for both authors and readers. Any author with an original story to share can go online, follow a few simple instructions, and in the time it takes to replace the word “paper” with “proton,” produce an ebook that can be accessed directly by a reader.

But is publishing an ebook really the same no-brainer step forward for my career as an author that word processing was for my writing?

No one really knows where the ebook revolution will lead. But it’s already had a radical effect on expectations, contracts, and the perception of self-publishing. Authors can now market directly, reaching out through our own websites as well as a variety of epub sites like Smashwords, Kindle, and PubIt. And readers have access to a much wider variety of stories—not just those in the same genre as the latest bestseller.

What’s not changing is the need for a great story. And a great story only surfaces after all the unnecessary words have been chipped away, which means that great editors are still needed too.

As more and more well-edited books appear in protons rather than on paper, the reputation of self-published ebooks will improve. After all, the reason self-publishing got such a bad name in the first place was the lack of quality control. Authors who give their work the same scrutiny a regular publisher would (or more) will quickly attract and maintain a wide audience.

I’ve heard from several authors that they’re selling more ebooks than they ever expected. Best of all, they’ve got much more control of their product than they would with a traditional publisher, and they keep a large percentage of the sales price. So what’s not to like about ebooks?

Here’s the downside. Protons can’t be “owned” in the same way a paper book sitting on a shelf can be, and they can’t be passed off to a friend. And as an author, holding an ereader in my hands that contains my book will never replace the tactile joy of holding the “real” paper copy.

So as both author and reader, I’ll embrace the ebook revolution—but I’m not ready to give up on paper without a backward glance, the way I gave up the typewriter a quarter century ago. If I really want to own or loan a book I care about, I’ll buy the paper copy. Because you can’t own protons; they belong to the world.

2 Replies to “Paperbacks or Protons: It’s Still All About the Story”

Comments are closed.